Asyla, Thomas Adès

It would be easy to forgive the critics who patriotically claimed Thomas Adès as the next Benjamin Britten, despite the composer’s squeamishness at the honour. By the age of 26, having rebelled against many of high modernism’s inflexible, academic ways of composing, Adès had already forged a highly individual end-of-century mainstream, full of postmodern wit and historical irony. Perhaps Britain’s historical lack of musical genius has provided him with a (not undeserved) fame usually reserved for dead composers. Asyla (1997) encompasses echoes of intoxicating late-Romanticism, a compelling, breathless narrative amid violent contrasts, and a grotesque orchestral reimagining of dance music, all while pursuing a single, elemental figure. The typically Adèsian wordplay of the title (implying places both of rest and for the mentally unstable) neatly captures the subversive tone of the piece.

An almost universal reaction to Asyla and to Adès’ oeuvre in general is his uncanny ability to make something simple sound strange and elusive – a basic interval or chord becomes a mass of possibilities, each pursued to its logical extremes. His music is characterised by the extreme organicism of his approach to development, the magnetic attraction he finds between two notes; notably when the chaconne-like harmonisation of the principal melody of the first movement begins to take on a life of its own, creating a complex, spiralling structure with the theme, or the bass oboe tune in the second movement which reframes the same intervals in an endlessly fascinating harmonic kaleidoscope.

The orchestra itself is here reimagined as a universe of colouristic extremes. Adès’ textural hallmark is being able to “compose in” an acoustic to the fabric of the music itself; the electrical energy of a city seems hard-wired into the potent orchestration of Asyla, just as his string quartet Arcadiana is acoustically infused with the simplicity of another age, making the quartet seem as though they are playing outdoors in an Arcadian country landscape.

There has always been a touch of the anti-establishment about Adès; an ability to be subversive in very public places. His eloquent critique of cliché and suspicion of generic formulae has long been a feature of his work; indeed he often cites his aversion to Wagner and Brahms for these reasons (see his witty “anti-homage” Brahms). He admits that “reality is always going to leak into the work to some extent” – questioning the basic premises of music, exposing the latent absurdity and surrealism of the art form (well suited to the idea of exploring these musical ‘madhouses’) is a key component of his musical mind. In terms of both form and content, the music perceptibly strikes a careful balance between extra-musical, cyclical, worldly experience, and a fantasia-like exploration of the subjective, musical ‘world of extension’. The work’s formal ambiguities and ceaseless musical argument raise many more questions than answers, leaving the listener enraptured by Adès’ unique and visionary world.

Below is a recording of Asyla, accompanied by a brief listening guide.

An ethereal introduction scored for cowbells and a piano tuned a quarter-tone flat prefigures the entry of the spectral, distant theme in muted horns at 0:45. Several intertwining melodic lines fight for attention before a fusion of the introduction and first theme at 2:38, with strands of leftover melody in the piccolo. An apotheosis of the omnipresent theme appears at 4:44, after parallel developments of the opening harmonic sequence supposedly based on Couperin.

The enigmatic second movement opens with a theme that Adès describes as “a knight’s move away from how a melody might normally work”, seductively scored for bass oboe (0:32). These hypnotic, descending two-note cells grow into passage for full orchestra before a magical moment of stasis at 2:43, where memories of the first movement’s emotional language of dissonance intrude. 4:37 looks both forwards and backwards, with an outburst prefiguring the third movement, just as the ‘knight’s move’ theme has lulled itself into the background, before we are left with thematic and harmonic debris to close the movement.

Adès wanted the third movement to “evoke the atmosphere of a massive nightclub with people dancing and taking drugs”, hence the double meaning of its title Ecstasio. Characterised by manic repetition, fragments of techno parody eventually cohere at 1:55. It is not hard to imagine the journey through the club, which is advanced very cinematically at moments such as 2:50 (and in all its glory at 4:20) leading to a climax quoting from the end of Act II of Parsifal. The atmosphere is all the more compelling because it crosses the threshold from the abstract “asyla” of the first two movements into the real (or surreal) world.

The finale is an aerial view of the whole piece, beginning with several frozen tableaux (an expressively dissonant wind duet at 1:11, and a ghostly, veiled piano solo at 1:42). In the footsteps of his hero Janáček, the movement is built on nothing more than a variant of standard ternary form, but richly patterned to form something very personal. 3:37 leads to a final, tempestuous search for the meaning of the opening figure, suggesting a circular resolution – a haven even – but one tinged with harmonic instability, neatly encapsulating the dichotomy at the heart of the work.

This fine recording is a product of the long-standing partnership of Adès and Simon Rattle, here conducting the CBSO. Rattle’s releases of his later music with the Berlin Philharmonic are similarly immaculate.

Adès has so far been influenced by an eclectic range of musics in his relatively short career. Tevot, written a decade after Asyla, is another creative summing-up of his formal inventiveness and ear for orchestral colour, and his Violin Concerto Concentric Paths is a thrilling exploration of the nature of musical form. The work of Julian Anderson, also at the forefront of young British composers, is similarly evocative and open-minded.

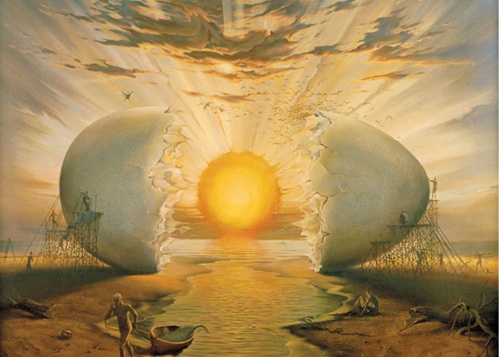

Artwork: Sunrise by the Ocean, Vladimir Kush

by Joel Sandelson

![gottlieb Ochre and Black [cropped]](https://articulatesilences.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/gottlieb-ochre-and-black-cropped.jpg?w=500&h=287)

![Kline Mahoning 1956 [cropped]](https://articulatesilences.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/kline-mahoning-1956-cropped.jpg?w=500&h=329)